Avoid a basic election analysis error with this one neat trick…

Don't build conclusions on voter movements from change in aggregate vote share

In the 2017 election, UKIP’s vote share fell and Labour’s rose by similar amounts. To some presenters of election night coverage, this indicated a substantial movement of voters from UKIP to Labour. This ‘fact’ established itself, including being repeated to me on several occasions, each time citing the broadcaster as the source when challenged, and the narrative demonstrably influenced the behaviour of Labour MPs later in the parliament, with a legacy to this day.

But the fact was never true. Data from the British Election Study and other post-election surveys showed that in actuality no more than one tenth of Labour’s voter gains came from UKIP, whose former voters were nearly four times as likely to have defected to the Conservatives. Labour’s largest partisan source of gains was in fact the Conservatives. The presenters had fallen for a type of ecological fallacy, inferring the behaviour of individuals from aggregate data. But they’re not alone. This error is frighteningly common within popular election analysis in the UK (and beyond). I’ve seen journalists, MPs and even political strategists make the mistake, with it on occasion managing to influence government policy. Luckily, it’s an easy mistake to understand and prevent.

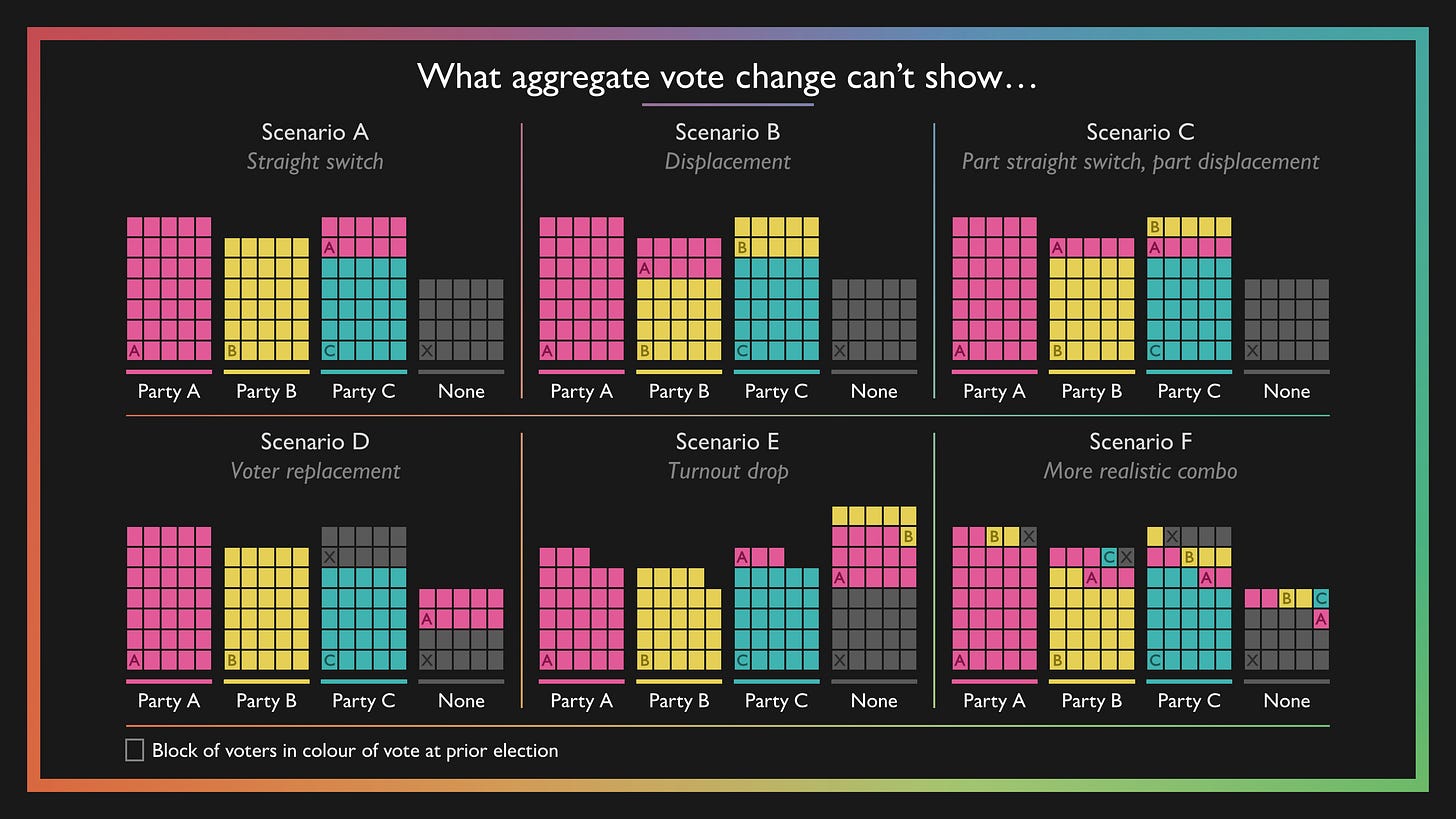

Imagine we have an election result where Party A’s vote share has declined by ten points, Party B’s has remained steady and Party C’s has increased by ten points. The answer might seem like it’s obvious, but the reality is that this is insufficient data to reach any conclusion.

Because while it might indeed be the case that the change is driven by Party A’s previous voters moving to Party C, there are multiple other scenarios that produce an identical change in aggregate vote share, as shown in the chart below. These include more complex chains of voters switching parties, as well as people moving between voting and non-voting (which can include ‘don’t know’ in inter-election polls). While, again, I can sense you wanting to say that the first is more valid or more likely, if your only information is aggregate vote change, all these hypotheses are equally valid.

No matter how tempting it might be, how obvious it might seem, you simply cannot build conclusions from aggregate vote change alone.

What you need is more information.

Correlations in lower-level aggregate data, such as at the constituency-level, can help, but there is also the possibility of ecological fallacies in this. For instance, if Party A’s vote share is declining more in constituencies containing a higher level of Demographic X, it could be the case that Party A voters from Demographic X are more likely to defect, but it could also be that Party A voters from Demographic Y are more likely to defect the more they live near Demographic X.

To actually be conclusive, you need individual-level data, which can be gained from sources like opinion polls and academic surveys, which are able to show which voters are moving and where they are going. Of course, they should always be used responsibly, with analysis preferably conducted by people who understand what surveys do and don’t say, but it can easily be done, including being integrated into things like election night coverage. It’s an easy mistake with a simple solution.

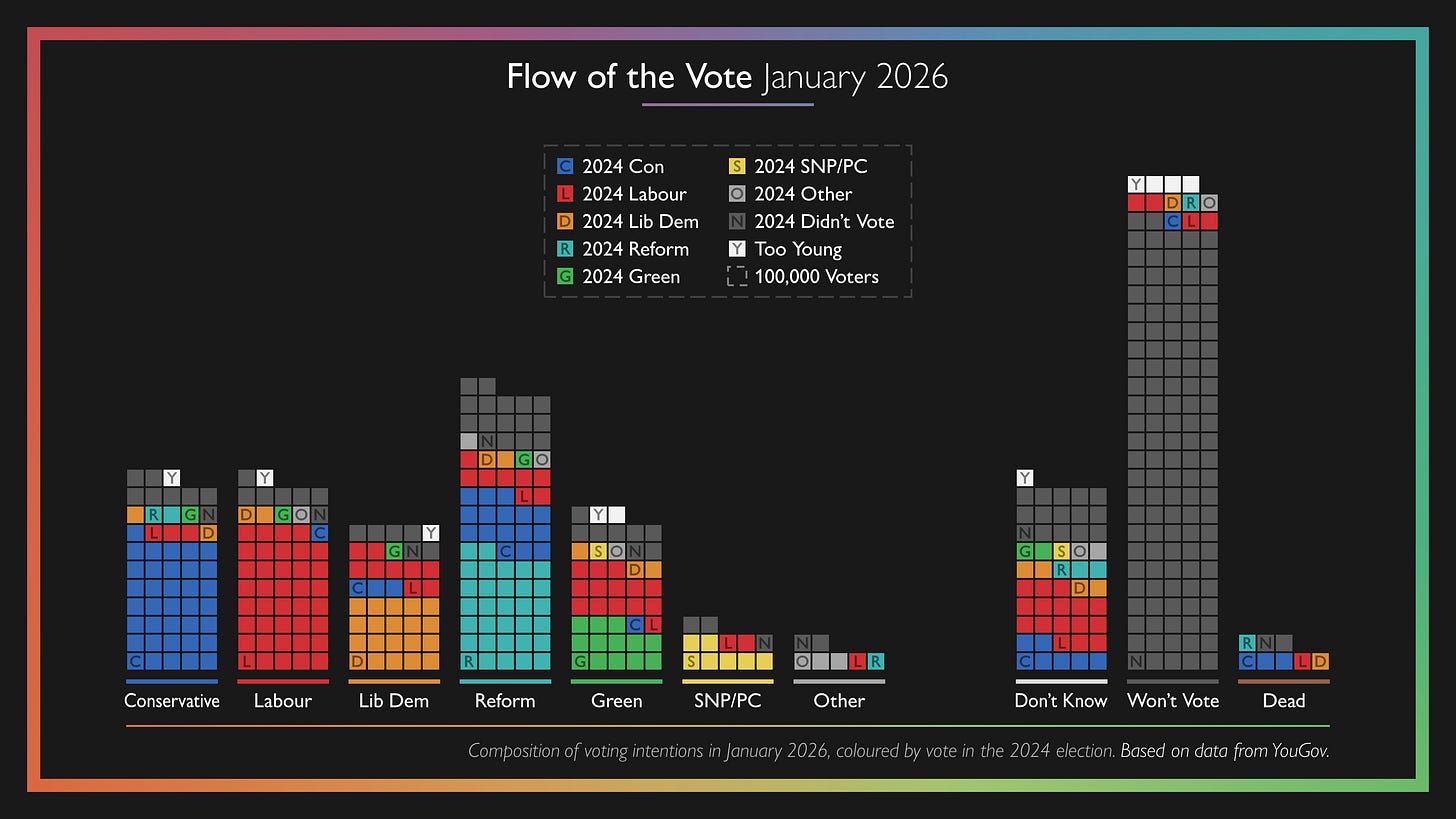

This, of course, has particular relevance to the current political moment, where you have significant movement of voters between parties and a significant amount of falling for ecological fallacies, sometimes even accompanied by the misplaced confidence that alternatives “cannot mathematically” be true. Examining the latest YouGov data shows that how voters are actually moving is indeed a little more complex than what aggregate vote change implies, as well as being a little Narrative™-busting.

Just one in six votes Reform UK have gained since the last election have come from Labour, with these voters representing little more than one in eight of Labour’s overall losses and just a fifth of Labour’s partisan losses. 2024 Conservative voters and previous non voters are greater sources of new voters for Nigel Farage’s party, while Labour voters are more likely to be now ‘don’t knows’ or to have switched to either the Greens or the Lib Dems.

In short, don’t build conclusions on voter movements from aggregate vote change. That’s not how that works.

This breakdown is extremly useful. The 2017 UKIP-to-Labour narrative became gospel despite being demonstrably false. What's wild is how often strategic decisions get made on these faulty assumptions becuase aggregate data feels intuitive. Individual-level polling data isn't perfect but at least it shows voter chains instead of letting us invent them from coinciding trendlines.